Blast from the past: Tunnel vision

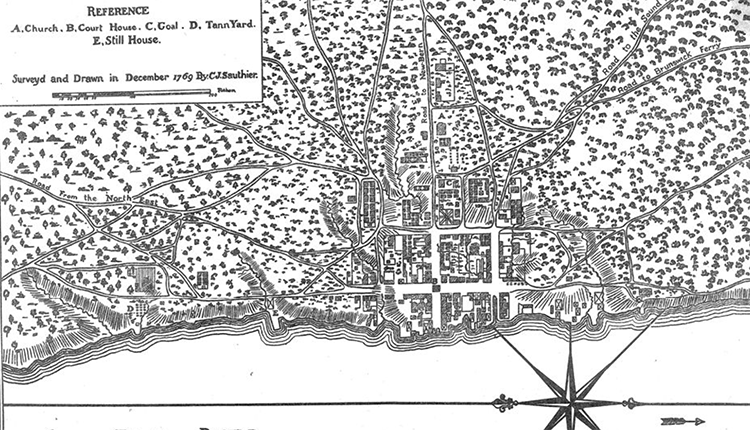

A 1769 map of downtown Wilmington shows the location of the streams that were rerouted into the brick passageways now located beneath city streets. (Courtesy of New Hanover County Public Library, North Carolina Room)

Editor’s Note: Blast from the Past is a recurring feature where stories from the Cape Fear region’s history are shared. This installment explores the enduring myths surrounding downtown Wilmington’s centuries-old network of underground tunnels.

Snaking through subterranean paths below downtown Wilmington’s historic houses and brick streets is a system of centuries-old tunnels that have long captured the imagination of both residents and visitors.

According to local lore, the tunnels were home to dramatic scenes in the city’s history: they allegedly allowed pirates to stash buried treasure for safekeeping, enslaved people to journey to freedom via the Underground Railroad, prisoners to enact successful jailbreaks, and lovers to sneak away for a moment of intimacy.

The mythos of Wilmington’s underground passages is the focus of a recent episode from the Burgwin-Wright House and Gardens' new podcast season. Titled “Cape Fear Legends & Lore,” the season explores enduring local legends. In “What Lies Beneath Wilmington,” host Hunter Ingram (who is also assistant director of the Burgwin-Wright House) discusses the sensational stories associated with the tunnels as well as the less romantic account of their origins.

Historical records indicate the tunnels were created in the 18th century as an engineering solution for a network of streams that crisscrossed downtown Wilmington. Early maps show around seven streams winding through city streets before emptying into the Cape Fear River. The streams frequently flooded, impeding the traffic crucial for some local businesses to attract and retain customers.

“They covered them up to create an easier way to get around Wilmington,” Ingram said. “This was the era of horses and carriages, so if there were larger streams – at least one of them was large enough to be navigated by boat – that would have limited development.”

The largest stream, Jacob’s Run, was deep and wide enough that boats could access a fish market near Market and Second streets or dock in the stream around what is now the intersection of Dock and Water streets (hence the former’s name).

The streams were long ago routed into the brick-lined passageways, and in addition to facilitating easier transportation of people and goods, the tunnels were also utilized to drain sewage from residences into the river – making them an unlikely candidate for a lover’s lane.

While historical records corroborating the more exciting uses of the tunnels are scarce, Ingram said there could be kernels of truth behind some of them.

By the time Wilmington’s tunnels were constructed, the so-called Golden Age of Piracy had passed, making it unlikely the tunnels were used by Edward Teach, Stede Bonnet or any other scallywags with links to the region. However, Ingram noted the Jacob’s Run tunnel empties into the river at the foot of Dock Street, near the historical location of the customs house. This makes it possible that some traders used the tunnel to sneak goods into or out of Wilmington.

“It’s likely that people could have smuggled things into those tunnels until nobody was watching, and then smuggled them into Wilmington,” he said.

Likewise, Wilmington’s tunnels would not have been a prudent option for enslaved people journeying to freedom, according to Ingram, because the tunnels cover a short span with known entry and exit points. However, they might have been used by urban slaves, who were often allowed more mobility and flexibility than enslaved people working on plantations, to secure a brief respite away from the eyes and demands of the people who enslaved them.

“Urban slavery was quite different from rural slavery. There was a bit more freedom for those who were working here in town,” Ingram said.

It’s also helpful to imagine these stories in the context of what the underground passages actually look like, Ingram noted.

“When people think of tunnels, they think of walking through tunnels like the catacombs underneath Paris or something like that. But the tunnels underneath Wilmington measure in inches, not feet. There are places that are literally just 24 inches tall,” Ingram said.

While some people have secured access to the tunnels in the past, all known entrances have been sealed as a safety precaution given both the tight quarters and concerns about the stability of structures built approximately 250 years ago. However, surprise entrances to the tunnels emerge from time to time in the form of sinkholes, like the most recent one near Market and Second streets in 2017.

“As much as I’d like to go down there, it does sound like a pain,” said Ingram, who tried to get a peek at the Jacob’s Run tunnel when he covered the 2017 sinkhole as a reporter for the Star News. “It sounds like the perfect place to flare up someone’s claustrophobia.”

Click here to listen to the Burgwin-Wright House’s podcast on Wilmington’s subterranean tunnels, or the newest episode exploring the legend of the iconic Dram Tree that allegedly stood sentinel from the banks of the Cape Fear River.